Azza Shoaibi

Hi team, it’s me again @AzzaShoaibi using @Gowtham_Rao account. This is day 11 of Phenotype Phebruary and I would like to start a discussion about suicide attempt. This is a phenotype that I worked on with my dear friend @conovermitch . In today’s post I will demonstrate:

- how important it is to learn from what others already did (literature) as a primary input into the phenotyping process

- how it is possible to incorporate other’s findings into OHDSI phenotyping practices and tools

- How we can but not necessarily should use “source codes” when developing phenotypes using OHDSI tools.

Suicide attempt/self-harm (clinical description):

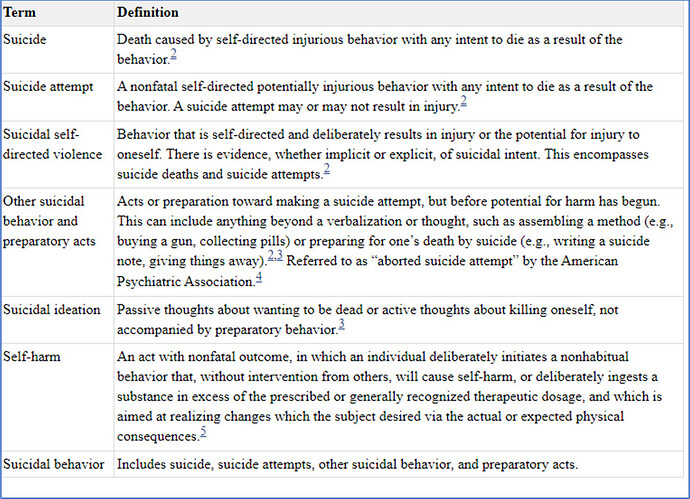

One of the biggest challenges when working on this phenotype is agreeing on the target/clinical description. Suicide is a major public health concern and there is a big debate on what is the right target for studies looking at suicide as a target (study population) or an outcome. There is multiple overlapping but different constructs/terms like: Self-harm, suicide attempt, suicide ideation/thoughts, suicidality overall, suicidal behavior.

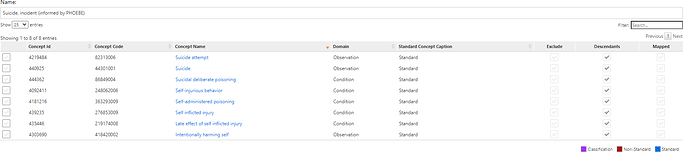

The table below from INTRODUCTION - Screening for Suicide Risk in Primary Care - NCBI Bookshelf provides a nice summary of the clinical definitions of these terms

I will try to simplify things here and set suicide attempt and/or self-harm (grouped) as my target-

What we know from literature about suicide attempt on observational data.

Many groups have looked into the utility of suicide related codes (mainly ICD-9 CM code) in claims data to identify patients with suicide attempts. I will brief my findings here”

• ICD-9 codes of E95* (injuries of intentional intent) are the most explicit diagnostic code for suicide attempts.

• Previous reports have indicated that ICD-9 codes matching E950* may have low sensitivity to detect suicidal behavior due to coding practices, reimbursement patterns, and the uncertainty of intent.

• To maximize sensitivity of the case definition, many have identified an additional set of ICD-9 injury code categories (that includes wounds and drug posing) and E98* (injury of questionable intent) as potential indicators of suicide attempts in medical records

• Different papers reported different PPV values for these additional codes For example, Barak-corren et al. Psychiatry Online reported poor PPV for E98* codes and demonstrated through chart reviews that E95* (positive predictive value: 0.82), 965.* (poisoning by analgesics, antipyretics, and antirheumatics; positive predictive value: 0.80), 967.* (poisoning by sedatives and hypnotics; positive predictive value; 0.84), 969.* (poisoning by psychotropic agents; positive predictive value: 0.80), and 881.* (open wound of elbow, forearm, and wrist; positive predictive value: 0.70) should be included. in contrary Simon et al Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death following completion of the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module in community practice - PMC reported that that inclusion of injuries and poisonings with undetermined intent (E98*) increases ascertainment of probable suicide attempts by approximately 25%.

• Coding of self-harm or possible suicidal behavior changed significantly with the transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM. ICD10-CM provides a higher granularity and higher opportunity to record suicide attempts and self-harm making it easier to identify intentional self-harm…

Cohort development:

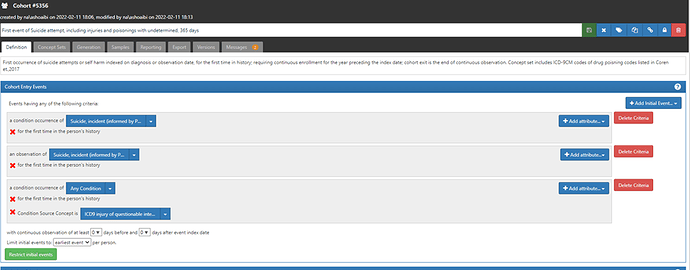

Considering this prior knowledge, I developed the following suicide attempts/self-harm cohort.

| # | Cohort | Standard code Codes used | Source of included codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | First event of Suicide attempt, 365 days prior observation | Earliest occurrence of suicide attempts using SNOMED standard codes (which translates/maps to E95* ICD-9m. | Phoebe informed |

| C2 | First event of Suicide attempt, including injuries and poisonings with undetermined intend, 365 days | Earliest occurrence of suicide attempts using SNOMED standard codes and ICD9CM codes for injury of questionable intent- E98* | Replicate Simon et al |

| C3 | First event of Suicide attempt, including drug poisoning arm injury, 365 days prior observation | Earliest occurrence of suicide attempts using SNOMED standard codes and ICD9CM codes for drug poising (965.* ,967.* 969*) | Replicate Barak-corren et al. |

Up to this point, we have been developing cohorts using standard codes only. The second and the 3rd cohorts above are using ICD9CM codes source in addition to SNOMED. You can do that in atlas by selecting the attribute condition source concept option from the drop-down list (+add attribute) at the right side- as shown below. In this case I used the source codes verbatim that were recommended by each of Simon et al and Barak-corren et al. instead of the corresponding standard code (as Patrick has done before in his examples of replicating cohort definitions from the literature). I had to do that because, 1. The recommendation of using ‘drug poisoning, wounds, and injuries with undetermined intent’ is specific to the US health care context in the era of ICD9cm. 2. These source codes map to general/broad standard SNOMED codes/clinical idea that will sweep in unrelated clinical ideas.

The use of source codes in the 2 cohorts above will only make a difference in data sources and times that ICD9CM is used. For example, in US based data sources the 3 definitions will be identical post the transition to ICD10CM era.

Cohort evaluation:

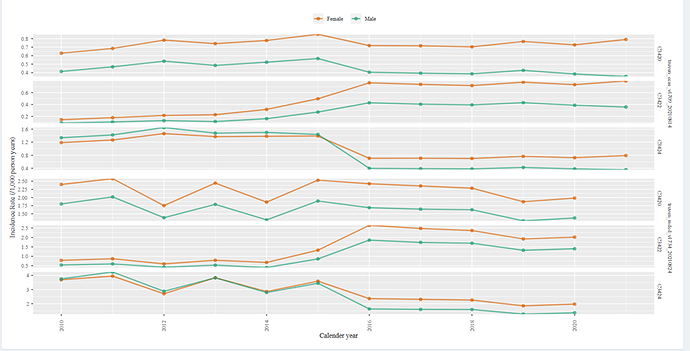

I will start here with incidence rate plot from cohort diagnostics

Above are results from 2 US based data bases (Optum EHR,DOD). C1 is showing a increasing trend post 2015. This is the cohort that is based on standard code and is consequently limited to the mapped ICD-9 codes of E95* (that we know have low sensitivity). The fact that we observe an increasing trend post 2015 suggest that the use of ICD10CM did indeed improve the systems ability to capture suicide in medical record (it is unlikely that suicide attempts and self-injury truly increased by 50%-80%).

The next question we can ask, does including additional set of ICD-9 injury code categories correct for the low incidence rate we observe pre-2015? In other words, will we see a stable incidence rate plot among C2 or C3?

We can see that both c2 and c3 has a much higher rate pre-2015, than that observe in c1, however, the line drops post 2015. The drop in c3 is milder than that in c2. This may suggest that using ICD9CM codes for injury of questionable intent- E98* resulted in a much higher rate than that observed post 2015 but using drug poising (965.* ,967.* 969*) resulted in a closer trend than that observed post 2015. We don’t know from here that the extra people added by using these drug poising codes are true suicide attempt cases, but we know that the trend became closer to what we observe post 2015.

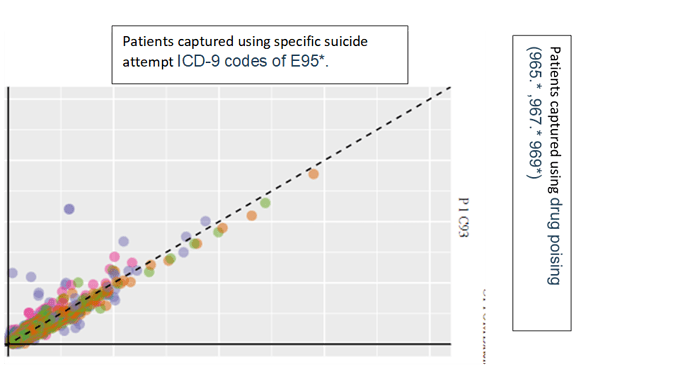

To check for what kind of people we are capturing we can explore temporal characterization. For this exercise, will look at a sub-cohort who met the requirement of C3 by having a code that belong to drug poising (965.* ,967.* 969*) [lets call it c93] and compare them to a subset of cohort who met c1 criteria through ICD-9 codes of E95*[lets call them c96]. This will help answer the question, are there similarities between those with specific suicide code and those with dug pointing codes , the plot below are taken from Optum DOD

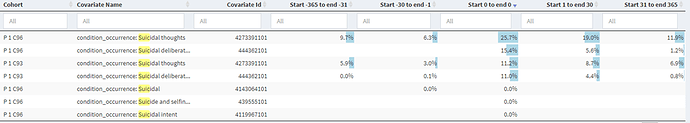

While the two groups are not identical there is considerable similarity in the covariate distribution. I will highlight some specific covariates that I investigated:

Please note that “suicidal thoughts” is not in the cohort definitions of neither of these groups. We observe that 11.2% c93 codes had suicidal thoughts. Interestingly, suicidal deliberate poising is part of c95 definition but not part of c93, however 11.0% of c93 has that code.

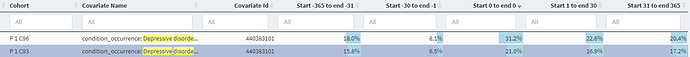

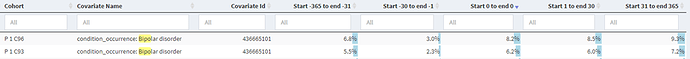

occurrence of depressive disorder, bipolar, alcohol use and opioid use were similar and relatedly common in both groups before and after index. These covariates may function as markers of specificity among these cohorts, observing consistent trends in the two cohorts (when they are mutually cohorts) is supportive evidence that icd9 cm drug poising codes may indeed be capturing patients with suicide attempts. Finally, age and gender distribution was similar across the 2 groups.

I showed 2 diagnostics in CD that are consistent (at least directionally) with prior findings of Barak-corren et al. and others that relied on chart reviews to estimate PPVs of specific codes.

Finally, I will quote my partner @conovermitch and his thoughts about any suicide phenotype, “suicide is a little different than our other phenotypes in terms of our expected capture in our data sources. Administrative claims and EHR data have fundamental limitations when it comes to capturing suicide and suicide attempts. Only a subset of suicides and suicide attempts result in medical encounters that appear in our data. This is important to think through in the context of whatever analysis you are doing since the misclassification can easily be differential with regard to disease severity (i.e. successful suicide attempts may never appear in the health system)

)

) :

: