Yes, definitely achieved the objective of ‘not completely unreasonable’

selection. Independent from that, having an empirical measure of

‘comparability’ could be useful, and in this case, could provide further

evidence for why the choices you made seem rational.

On http://forums.ohdsi.org/uploads/default/original/1X/8149c12c06bcb0ed3c41b050d2509dc6479b45b2.xlsx NegativeControlOutcomes.xlsx, you dropped some I might not have thought to drop but that’s fine.

George

Thanks George!

Anyone else who can help review these negative controls? We really want to be sure about their negative status. I would like to prevent others from writing papers like this.

I started working on the negative control exposures for our outcomes of interest. I started with acute pancreatitis, and found it to be much more work than anticipated. The main reason was that many things appear to cause pancreatitis, or at least have an unclear link. I found this paper to be very helpful.

Here are the steps I took:

- In ATLAS, I created a concept set for acute pancreatitis

- I went to ‘Exlore evidence’, generated evidence on drugs related to this outcome

- I restricted to the subset of negative control candidates

- I then linked this information to the information extracted from clinicaltrials.gov to identify target-comparator pairs where both drugs are candidate negative controls for AP.

- I ordered the list by the minimum of the count of people on the target drug and on the comparator drug.

- I manually reviewed the list until I reached 25 negative control target-comparator pairs.

Here is my list:

NcExposurePairs.xlsx (16.5 KB)

I’m afraid some of the pairs lower on the list have very little prevalence, so we may need to rethink our strategy. Anyone want to help out and look at these?

Note that griseofulvin is mentioned in the review below. It seemed kind of suspicious as it causes a lot of things. George

Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001 Sep;57(6-7):517-21.

Spontaneous reports on drug-induced pancreatitis in Denmark from 1968 to 1999.

Andersen V1, Sonne J, Andersen M.

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To present an update on drug-induced pancreatitis reported to the Danish Committee on Adverse Drug Reactions.

DESIGN:

Retrospective study of spontaneous case reports to the Danish reporting system on adverse drug reactions.

METHODS:

All cases of suspected drug-induced pancreatitis reported to the Danish Committee on Adverse Drug Reactions from 1968 to 1999 were analysed. Three cases were excluded leaving 47 cases for analysis.

RESULTS:

Drug-induced pancreatitis made up 0. 1% of all the reports to the committee from 1968 to 1999. The proportion seemed to increase and was 0.3% during the last 8 years. The 47 cases corresponded to 0.1% of the number of patients discharged due to pancreatic disease (without cancers) per year in Denmark. Serious courses were frequent as indicated by death and hospitalisation being reported in 4 (9%) and 32 (68%) cases, respectively. Death occurred after valproate (two cases), clomipramine (one case) and azathioprine (one case). Definite relationship was stated for mesalazine (three cases), azathioprine (two cases) and simvastatin (one case) on the basis of re-challenge. A possible or probable causality was considered for a further 30 drugs including 5-acetylsalicylic acid agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, estrogen preparations, didanosine, valproate, codeine, antiviral agents used in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome therapy, various lipid-reducing agents, interferon, paracetamol, griseofulvin, ticlopine, allopurinol, lithium and the MMR (measles" mumps/rubella) vaccination.

CONCLUSION:

Drug-induced pancreatitis is rarely reported. The incidence may be increasing and the course is often serious. This is the first report on definite simvastatin-induced pancreatitis. Further studies on the pancreotoxic potential of drugs are warranted.

Urghh, according to this paper that is based on 1 spontaneous report with ‘possible or probable’ cause. But better safe than sorry, so I’ll take it out. Thanks!

I’ve added another heuristic for finding comparators in the hope of finding ones that have higher prevalences. The new heuristic is simply based on ATC codes: a comparator is a drug where the first four digits of the ATC code match (same indication) but the 5th doesn’t (different class). I’ve implemented this in the Amazing Comparator Finder, and it seems to work nicely.

(note: I restricted to one ATC code per ingredient, the most prevalent one)

I’ll proceed by using this to find additional negative control target-comparator pairs for acute pancreatitits.

First, ‘the Amazing Comparator Finder’ is truly amazing! Great work,

Martijn. Very impressive!

Second, it seems like ‘placebo’ is a really good comparator a lot of the

time. It’s a shame it doesn’t have a ATC code, otherwise, we should really

try to find that drug in the database

I don’t know, I’ve heard very bad things about placebo. I think it causes a lot of outcomes!

Just finished redoing the negative control exposures for acute pancreatitis, this time using both clinicaltrial.gov and the ATC heuristic to select comparators. Adding the ATC heuristic allowed selection of target-comparator pairs with signficantly higher prevalence, so overall I feel much better about this list:

NcExposurePairs.xlsx (28.4 KB)

Amazing job. You know, I cannot find a drug on the list that the Internet does not accuse of causing pancreatitis in rare cases. (Tadalafil, levodopa, ivermectin for the three I checked.) So no matter what we pick, there will be an assertion by someone that they are false negatives. We need to be clear about the formal criteria we can publish to support out argument.

George

I’ve considered pretty much any evidence that suggests causality, except sites like ehealthme.com and patientsville.com.

Could you share the evidence you found for tadalafil, levodopa, and ivermectin?

Ehealthme is the kind of thing I am talking about. I am saying that we are right, but there may be pushback generated. George

As a general rule I’m only considering evidence of causality. A report (either official in FAERS or unofficial in sites like ehealthme.com) of co-occurrence of the treatment and the disease is not considered evidence of causality, unless the rate of co-occurrence is higher than expected (ie. a PRR that is significantly higher than 1).

Anyway, something like that should be our defense against any pushback. I think especially those two sites simply link every drug to every outcome, so by definition they are uninformative.

I’ve now also added negative control exposures for GI bleed and stroke:

NcExposurePairs.xlsx (43.2 KB)

LAERTES was very restrictive for GI bleeding meaning most candidates looked good but had low numbers of users.

I’ve now also added IBD. Here is the final set of negative control exposures I came up with:

NcExposurePairs.xlsx (66.2 KB)

And for completeness the set of negative control outcomes posted earlier:

NegativeControlOutcomes.xlsx (504.2 KB)

I wrote some quick-and-dirty PubMed queries to catch any major blunders:

VerificationPubMedQueries.xlsx (10.7 KB)

Which led me to drop levodopa as a negative control exposure for acute pancreatitis (and added a new one). Otherwise I can find no major issues. However, I would really appreciate more people reviewing these sets!

I just realized we also need nesting cohorts for every exposure (pair), for example to evaluate the nested case-control design.

I’ve added a new feature to The Amazing Comparator Finder: Finding common indications for a target-comparator pair. I’ve used a simple data-driven approach based on occurrence of a condition code on the same date as initiation of a treatment.

I intend to use this feature to find nesting cohorts for all out negative controls, since studies are typically nested in a specific indication. This is especially important for the nested case-control design, but also other designs often restrict their population to a specific indication, and we would like to evaluate performance when such restriction is present.

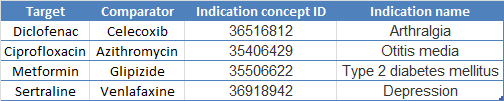

Here are the indications I picked using this tool for our four exposures of interest:

Now I just have 100 negative control exposure pairs to go!

Here it is! The full set I’ve generated so far, including nesting cohorts for those methods that need them. Now I just need to find some poor souls to review this.

FullSetOfNegativeControls19May2017.xlsx (23.7 KB)

Note that this set is intended to be used both for evaluating methods focused on the risk of a single treatment, as well as methods that compare risk between treatments. For the first type of methods, one can simply ignore the comparators I selected.

I’ve created definitions for our four outcomes of interest based on the algorithms described in the Mini-Sentinel HOI library:

I’ve made it so that the list of ICD-9 codes these definitions map to are identical to the lists of codes mentioned in the Mini-Sentinel definitions (for better or worse).

Some things worth discussing:

All these definitions except for IBD require diagnose codes to be found in the primary position for an inpatient (or ER) visit. This means that some databases (e.g. primary care databases) will not be able to pick up these events using these definitions. Should we maybe broaden the criteria? Add additional definitions for different databases?

For the negative control outcomes that are not part of the four (ie the wide set associated with the exposures of interest) we typically just look for occurrences of the main concept or any of its descendants in the data. Should we force them to be restricted to hospitalization codes only?

have you considered ‘negative control’ time windows (instead of outcomes or exposure/s)? we’ve used this recently to identify residual confounding. in our example, we showed that bisphosphonate users have an increased fracture risk even after propensity score matching, and -fundamentally- they have an increased fracture risk from day 1 of therapy. trouble (or key concept) here is that bisphosphonates don’t have any effects on bone for at least 3 months, as it’s known from pre-clinical and clinical RCT data

anyone interested in this let me know. you could potentially replicate eg for statins and mi at the population level…